Book of Knowledge

Chapters: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

List of all languages referred to in the Book of Knowledge and other sections of the website.

DOWNLOAD and print out the Book of Knowledge.

Chapter author: Maciej Karpiński

Chapter contents:

Different languages, different sounds

Different sounds, different manner of articulation

Strange sounds of strange languages

Sound classes: phonemes

Tone and intonation

Accent and rhythm

Archiving and reconstructing sound systems

How to transcribe sounds of a language?

Visible sound

Less widely used languages and technology

Notes

References & further reading

Different languages, different sounds

It is often said that languages differ by sound or melody. What does this mean? Only when one begins consciously the process of learning a foreign language, does one notice that the language in question possesses sounds far removed from those in one’s own, and not even produced in the same manner. Sometimes, there are also sounds which sound similar, yet prove to be different by a minute, but essential, detail. Those sounds cannot simply be replaced by sounds one knows from their own language. Such a replacement could change the meaning of a word or phrase, or even cause the sentence to become incomprehensible. Correct articulation can prove to be of great difficulty and may require arduous and repetitive practice. Several different sounds may sound the same to a non-native speaker, and at the same time, deceptively similar to a sound from their own mother tongue. Although awareness of such phenomena increases with every new foreign language learnt, only a few realise just how much variety of sound exists in the languages of the world.

Different sounds, different manner of articulation

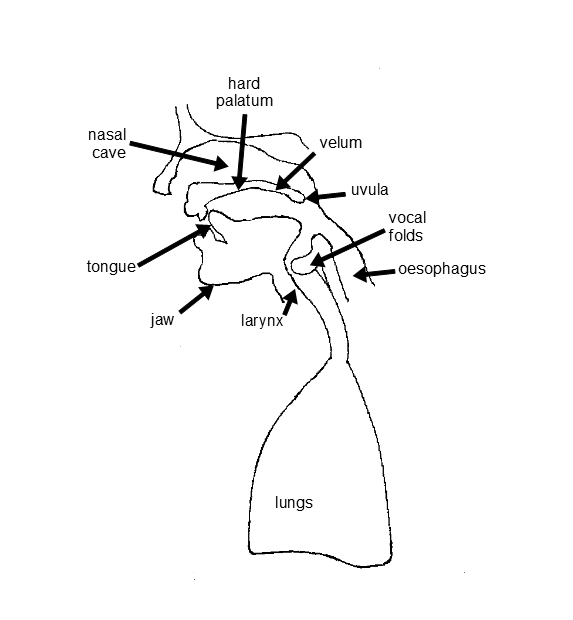

The differences in sound are the result of different manners of articulation – the way they are pronounced. Speaking in a native or a second very well-known language doesn’t require much thought about the positioning of the lips, the tongue or a possible closing of the air flow through the nasal cavity. Fully conscious articulation would be too slow. There are only a few elements whose position can be controlled by conscious will (see the figure below). Nonetheless, it still allows a great variety of sounds to be pronounced. Apart from speech, this can also be observed, perhaps with greater ease, in singing. Each natural language uses but a small part of the great phonemic potential. As such, languages usually consist of only several dozen such sound units, which are then used to build sentences.

It is mainly the vocal folds which are responsible for voicing and pitch. The process by which the vocal folds produce certain sounds is called ‘phonation’. It is possible to feel them vibrating by placing fingers on one’s Adam’s apple. Women’s vocal folds are of a smaller size than those of men. The rest of the vocal tract (its exact shape differs from person to person) decides on what sound is to be initiated. The changes (be they conscious or automatic) during the articulation process also influence the produced sound. Vowels are the sounds produced with a widely open articulatory channel. If in the process of articulation, an obstruction occurs in the vocal tract (i.e. the tongue touches the palate, the mouth is closed), the produced sound is a consonant. The sounds ‘in-between’, articulated with a narrowed vocal tract are called approximants (for example the English sounds which are represented in orthography by the letters and , and in phonetic alphabets by the same symbols [w] and [j]. In a sense, they are a bit like ‘uncompleted vowels’).

Strange sounds of strange languages

‘Strange’ is of course a term used half-jokingly here and should be understood rather as ‘rare’. The readers of this text are probably familiar only with major European languages, thus they might find some of the articulation phenomena or sounds existing in languages of Asia and Africa quite different from their own.

It is often assumed that vowels are always voiced as that is the case in the most commonly spoken languages in Europe. When whispering, however, the vowels of the aforementioned languages can be rendered voiceless, all the while remaining comprehensible and distinguishable. Nevertheless, such cases occur rarely. Languages whose sound systems comprise voiceless vowels include American Indian languages like Zuni [1] or Cherokee [2], or languages from the Totonakan language family from Mexico. Laryngealization can be regarded as a particular voice quality. It is realised as a kind of croak, especially at the end of sentences. It appears when the vocal folds vibrate irregularly as a result of low volume-velocity of the air flow. There are, however, languages such as Kedang (an Austronesian language spoken in Indonesia) or Jalapa Mazatec (spoken in Mexico), where a creaky voice is an important sound quality. Although aspirated consonants are quite popular and exist in many languages of the world, aspirated vowels present in Jalapa Mazatec or Gujarati [3], remain quite a rarity.

When speaking of rare sounds, clicks are often mentioned. They occur mainly in the languages of Southern Africa, but not exclusively since they are also known to be present in a ceremonial language called Damin, which used to be spoken in Australia. Here you can find a video clip introducing the four click sounds of Khoekhoegowab [4]: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nz44WiTVJww

TRY AND CLICK

Try producing these sounds! It may be easy in isolation, but it will prove far more difficult in continued or uninterrupted speech. Undoubtedly, native speakers will not have any difficulty in articulating the clicks, even when singing.

The South African singer Miriam Makeba popularized clicks with a song in Xhosa [5], which originally is called “Qongqothwane” but outside Africa is known as “The Click Song”.

CLICKS IN XHOSA

Watch a performance of Miriam Makeba’s song here, with introductory remarks by the singer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3m_TEq2E4cs

In transliterations based on the Latin alphabet, a click may be transliterated by using an exclamation mark (see examples in the next subchapter).

Go to the Interactive Map and try exercises for Taa and !Akhoe languages.

Sound classes: phonemes

As is apparent, every language can possess a different set of sounds which, in turn, are differentiated by various features. Traditionally, researching the phonetic inventory of a natural language relies on observing the context where the particular sounds appear and also their influence on the meaning of a given phrase. Thus, the so-called minimal pairs are being sought after. Minimal pairs are pairs of words which differ from each other only by one single sound, such as Polish dama ‘lady’ and tama ‘dam’. The same type of differing qualities between phones can be essential in distinguishing sound classes in one language, and completely irrelevant in another. If a change of one phone in a word carries a change in meaning and it changes into another, separate word, it means that this feature is phonologically important. Thus, those two phones belong to different classes – they represent different phonemes. Those changes are often connected to the place and manner of articulation. Voicing is a distinct feature in many languages of the world. In Polish, for example, the words dama and tama begin with phonemes that differ only by the fact that the former is voiced, and the latter voiceless. It is phonation that decides the meaning of the word. In some languages, the length of the sound is of high importance. Most often, there are long and short vowels (for example in Hindi). Two words may mean something different because of one vowel’s length (such as German raten ‘to advise’ and Ratten ‘rats’, or English beat vs. bit). There also exist languages in which it is consonant length that is of great importance. In Polish, vowel length is used, amongst other things, to enhance comprehensibility or expressiveness of the sentence (for example, in the question co? ‘what’, the vowel can be lengthened to indicated astonishmet: coooo?). Longer or shorter segments do not, however, change their lexical meanings simply because of the length (just as co, also coooo means ‘what’).

Phonological systems are abstract systems, functioning in human minds and containing information about the phonemic inventory of a given language. Such a system comprises of the already mentioned phonemes. A phoneme is a unit that can differentiate meaning even though it does not have a meaning on its own. Phonemes do not carry a meaning, unlike words or sentences. The number of phonemes in languages is astonishingly varied, from a dozen or so in Rotokas [6], Piraha [7], or Ainu [8] to more than a hundred in Taa (also known as !Xóõ or !Xuun – the exclamation mark representing one of the clicks), one of the Khoisan languages spoken in South Africa. Irish [9] also possesses a formidable phonetic inventory of 69 phonemes. The usual number, however, is between 20 and 60.

Learn more

Learn more about phoneme inventories in the languages of the world in the World Atlas of Language Structure at http://wals.info/chapter/1 and http://wals.info/chapter/2

Traditionally, phonemes are grouped into consonant phonemes and vowel phonemes. Nevertheless, there are those that lie somewhere in-between (approximants). Most often, there are many more consonant phonemes than vowel phonemes (such as in Polish or German), though exceptions do exist. One such exception is the Marquesan language (a cluster of East-Central Polynesian dialects) in which the number of consonants and vowels is comparable. Samples of Marquesan are available on the language documentation project’s website, including a recipe for crispy octopus: http://www.mpi.nl/DOBES/projects/marquesan/data. An already extinct language, Ubykh, has eighty two distinct consonants, but only two distinct vowels. Those vowels, however, could be pronounced differently, depending on their phonetic environment. The language that holds the title of the one possessing the largest number of vowels is Taa, whose one dialect distinguishes between thirty one vowels.

Linguists believe in a complicated system, residing in the mind, which stores all the information about units of a language. It is called the ‘mental lexicon’, but its functions and structure differ markedly from an ordinary dictionary. It is tentatively agreed that every known word is stored in the mental lexicon as a phonemic transcription – a sequence of phonemes. By pronouncing it, all the particular phonemes are being realised. They are transformed from being abstract ideas into concrete, physical and perceptible sounds; they become phones. Changing a sequence of phonemes into a sequence of phones is not an easy task, however. During this process, many phenomena may occur, depending on the context and other factors, which may result in the actual word being pronounced a bit differently. The phonemes could be realised in another way, for example due to neighbouring sounds, and yet the meaning would stay the same.

A sound system of a language is not simply an abstract set of phonemes and rules of their realisation in different contexts. It is also a collection of phonotactical restrictions on the permissible combinations of phonemes. Many languages are fond of planting vowels in between consonants. Some, however, do allow unusually complex consonant clusters (i.e. Polish pstryknąć or Czech čtvrtek). The presence of such a cluster in English would surely seem suspicious to a native speaker. As a result, it is not possible to guess the possible inventory of syllables in a language by forming arbitrary pairs, triples etc. of its phonemes. The actual number of possible syllables is much lower than this hypothetical number.

Exercise

Try writing down all the sounds of your own language. Do not pay attention to the writing system or the number of characters in it. Do any pairs or triples of those sounds, placed one after another, sound out of place in your language?

Tone and intonation

Apart from phonemes, there are also other elements of the sound systems which may influence the meaning. In tonal languages, every syllable is pronounced with a certain melody to it – its tone. Change of a tone on a given syllable may change the meaning of the word, be it a mono- or polysyllabic word. If indeed a syllable’s tone can modify the meaning of the word, it is called ‘lexical tone’.

The example below from Mandarin Chinese is often cited to illustrate the idea of tonal languages. The sound sequence /ma/ has a variety of distinct meanings, depending on the tone chosen.

- mā 媽mother (level tone)

- má 麻hemp (high-rising tone )

- mǎ 馬horse (high-falling tone)

- mà 罵scold (low tone)

When talking about tonality, the languages of Southeast Asia, such as Mandarin Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai etc., are most often, even though two other continents, North America and Africa (especially in the central west areas) also provide an abundance of such languages. Lexical tone is present, for example, in the Yaka language (a Bantu language of central Africa):

- mbókà – village

- mbòká – fields

- mbóká – civet (mammal from the viverrid family)

(data from Kutch Loyenga 2011)

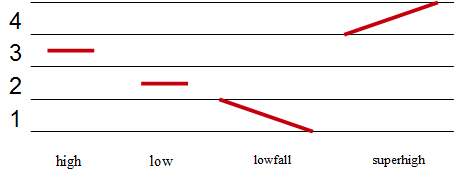

Cherokee [10] is an exemplary tonal language from North America. It is generally considered to have four distinct tones:

According to some researches, the tones are gradually disappearing in Cherokee.

Tones (the melody of the syllable) may also have other effects on the language, such as serving grammatical functions. Here is an example of the Ngiti language spoken in the Democratic Republic of the Congo:

- ma màkpěnà ‘I whistled’ (recent past)

- ma mákpěná ‘I whistled’ (intermediate past)

- ma makpéna ‘I will whistle’ (near future)

- ma makpénà ‘I used to whistle’ (past habitual)

- ma mubhi ‘I walked’ (distant past)

- ma mubhi ‘I walked’ (narrative past)

(The tones here have been transcribed by the following diacritics: á – high tone, à – low tone, a – neutral tone, ǎ – rising tone; Kutsch Lojenga 1994)

Non-standard phonation which does not rely on vibration of the vocal folds to produce sounds may cause a problem with choosing an adequate pitch and its variation. This, in turn, might interfere with identifying the particular tone. In those few languages which feature both of these two phenomena (tones and non-modal phonation), contrastive pairs between them are rare indeed.

Many of the European languages are based on intonation. In those languages, variation of pitch does not change the basic, lexical meaning of the word. It can be used to express the speaker’s attitude or emotions. Sentence intonation can be used to discern the purpose of the phrase (i.e. differentiate between questions or declarative statements, etc.). Intonation exists in tonal languages as well, but it generally needs to be subordinate to the tones (although this claim is still under discussion). A ‘hybrid’ language, in which intonation co-exists with lexical tonality, such as Cherokee, is a rare oddity.

A question

Is your own language tone- or intonation-based? If it is an intonation language, do you think it is possible it has ever been a tonal one? What about the other way around?

Accent and rhythm

Syllabication does not present a problem for most people, even if at times their intuitive syllabification skills prove wrong according to the rules of a given language. For a linguist however, a syllable remains a very difficult unit to define. Likewise, a native speaker can easily recognise that some syllables are more sonorous or prominent than others in their immediate vicinity. Still, a precise definition of this sonority remains difficult to pinpoint.

In this context, the concepts of accent, stress and emphasis are worth mentioning. Browsing through entries in dictionaries of English, German, Polish or other languages, one may find specific indications as to which syllables are to be (or may be) accentuated/stressed. It is possible that when dealing with a particularly long word, there may be more than one prominent syllable. One of them will carry the primary (i.e. strongest) stress, while the others represent a secondary or tertiary etc. (i.e. weaker) stress. The particular syllable where the lexical stress falls can be described as a ‘potential position of accentuation’. Consequently, it is possible to pronounce a given word while placing stress on a different syllable, even if at times it may be difficult to do so. Most often it also leads to an erroneous pronunciation or problems with comprehension. The position of stress may be a result of the word’s morphological structure, or it may be fixed. For example, the stress falls on the first syllable of a word in Czech, on the final syllable in French, and on the penultimate syllable in Polish. There are also languages, such as Korean, that do not use lexical stress. Instead it only appears within phrases or sentences used to perform certain functions. Some languages are said to have variable stress, such as in the case of Russian. In certain languages a change in position of the stress carries a change in meaning. In English, research with stress on the first syllable is a noun, while on the second it is a verb. How does it work in your own language?

There are several ways to mark a syllable as prominent and make it stand out from the others. It can be pronounced more loudly, it can be said with an altered pitch, or it can be lengthened. Alternatively, any of the aforementioned methods can be applied in any combination. Try listening to your own speech and think about which of the techniques are used in your own language. Perhaps record a few spontaneously uttered sentences and then listen to them carefully.

Thanks to the features of particular syllables, such as sonority, length or sequentiality, a certain rhythm arises. This kind of rhythm is slightly different from the well-known musical rhythm which is associated with constant repetition of the same musical patterns. Such repetitiveness is very rare in a language, orit can only be found in poetry, song lyrics and melodeclamation. However, rhythm does exist in language. Listening to English and French and then imitating the speech patterns whilst substituting ‘da’ and ‘dam’ for actual words allows one to notice the distinct differences between the rhythmic systems of the two languages. According to one of the hypotheses, rhythm-wise, languages can be grouped into two categories: syllable-timed and stress-timed. In the case of the former, the rhythm of speech is governed by a tendency to maintain a constant syllable length, in the latter, a constant interval between the stressed syllables. Nowadays, however, this theory is criticised more and more frequently, but it is important to be familiar with it. Perhaps you will be able to discern which of the two categories applies to your own languages (see also: Appendix).

Archiving and reconstructing sound systems

One of the main contemporary methods of documenting a language relies on the recording spoken texts (see Chapter 9 for more information about this process). Sound systems of languages long dead can be replayed and analysed anew owing to such a database of recordings. The first mobile recording devices (Nagra reel-to-reel recorders) were invented in the 1960’s (read about them on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nagra), but it was not until the following decade that relatively cheap and light cassette deck recorders became available to the general public. Although there exist recordings of dying languages which date back to the previous century (i.e. Bronisław Piłsudski’s wax cylinders used to record speakers of the Ainu language; learn more about Bronisław Piłsudski here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronisław_Piłsudski), they remain very rare. How, then, is it possible to reproduce the sounds of a language which has ceased to be spoken? If the language in question was written in an alphabetic script, it might be possible, if still very difficult. How can one be sure of the correlation between the signs and sounds? In many cases, such attempts require vast knowledge and extensive research far beyond the matters of the given language only. The questions to ask are: what other, better-known languages or cultures imposed their influence on it? Do any presently-spoken languages originate from it? Are there any similarities in sound due to the same linguistic origin?

It is also important to note that spoken language differs from written language. The differences are far more striking than the utilisation of prosody and pitch in speech. Written texts are usually more orderly, neat, thought over and grammatically consistent. Thus, even if written documents in an extinct language exist, recreating how exactly the language was spoken in everyday situations remains demanding, if not impossible. This is just one more argument for keeping linguistic corpora and databases of speech in all languages, but even more so in those less widely used or close to extinction.

How to transcribe sounds of a language?

Phonemic recording of spoken texts is no longer a technically demanding task (see Chapter 10: Language documenting), but its written record is also needed for many purposes. This kind of written text linguists call ‘transcription’. It is often very different from an orthographically written text.

There is no correlation between the graphic signs of a language and its sounds in many languages of the world. Their writing systems do not pertain to the actual sounds of the written texts. The signs might represent whole words and thus, they do not show the reader of what sound units those words comprise. One could expect the highest level of correspondence between graphic signs and sounds from languages based on an alphabetic script, such as Latin (which, in one form or another, is used by most European languages). Even here, however, one encounters difficulties as one letter may signify different sounds and be read in various ways. In English, a double o is pronounced differently in blood, book and door. The fact that sometimes up to four letters are used to represent a single sound (for example, in though) may also leave one wondering. Writing systems of natural languages are usually based on tradition and in many cases they prove difficult for linguists to analyse. Moreover, many languages, especially the less widely used or endangered ones, do not even have a writing system. Therefore, there was a need for a universal, well-planned system for writing down the sounds of speech. This system could be used equally well to write utterances in a known as well as an unknown language, as it would be capable of noting down sounds of almost any thinkable manner of articulation. The phonetic transcription system of IPA (International Phonetics Association; homepage of the IPA: http://www.langsci.ucl.ac.uk/ipa/) fulfils all those requirements. It assigns particular symbols to every possible configuration of the articulators (see: above). An overview of the IPA symbols can be found for example here: http://www.phonetics.ucla.edu/course/chapter1/chapter1.html. The system itself is extremely advanced and its use requires a lot of time and effort spent on mastering it. Even experienced phoneticians may not always agree as to the phonetic transcription of a particular utterance, because the system is binary and absolute. A given sound can either be voiced or voiceless, nasal or non-nasal. In practice, however, a phonetician knows that nasality or voicing are gradable in actual speech and it might be difficult to decide whether the feature has already appeared or not (i.e. if the given segmental is voiced or not).

Knowing the phonetic inventory of a given language (i.e. the set of its ‘basic sounds’), it is possible to transcribe speech in a less complicated manner. A broad (or phonemic, phonological) transcription takes into consideration only the phoneme which the particular sound of the utterance corresponds to. In this case, the articulatory details of the speaker are irrelevant. Only the key elements such as features differentiating the sounds matter. The transcription only contains the number of symbols needed to transcribe all phonemes of a given language. It is, thus, language-related, although at times it can serve a larger number of languages with similar phonological systems. A native speaker can use it without the arduous training required to master the phonetic transcription (narrow transcription). It can still prove difficult to a person who does not know the language in question as she may not be familiar with what the important features differentiating segments in the given language are. Neither will she know how to assign them to particular phonemes.

In view of some of the unusual symbols of the IPA, some phoneticians decide to use different symbols, based on combinations of letters known from the Latin alphabet. This system is known as SAMPA. It is most often used for broad transcription. SAMPA has been adapted to many languages and thus, there are various ‘national’ variants of this kind of notation. (You may read more about SAMPA here: http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/sampa/).

When necessary, however, linguists may use transcription systems based on the orthography of the given language. Some additional symbols might be added, thanks to which one can transcribe phenomena such as yawning, silence, interjections or to specify the voice quality (i.e. creaky, high, whisper). Some decide not to include punctuation, capital/small letter distinction (if such a distinction exists in the language) or other orthographic rules so as to minimise arbitrariness and subjectivity. Transcription, however, always remains a subjective interpretation of one’s speech.

Here is an example using three different manners of transcription – orthographic, IPA and SAMPA for a phrase “Pewnego razu Północny wiatr sprzeczali się“. To facilitate comparison, the short text was divided into syllables. It is, however, a broad, hypothetical transcription as it can be realised differently (for example by keeping the last segmental nasalised).

| Zapis ortograficzny | pew | ne | go | ra | zu | pół | noc | ny | wiatr | i | słoń | ce | sprze | cza | li | się |

| IPA | pev | ne | go | ra | zu | puw | noʨ | nɨ | vjatr | i | swoɲ | tse | spʃe | ͡tʃa | li | ɕe |

| SAMPA | pev | ne | go | ra | zu | puw | not^s | ny | vjatr | i | swon’ | t^se | spSe | t^Sa | li | s’e |

*) A slightly adapted version of the Polish SAMPA has been used here. It was prepared by J. Kleśta to limit ambiguity caused by the same symbols being used to represent different sounds in different languages

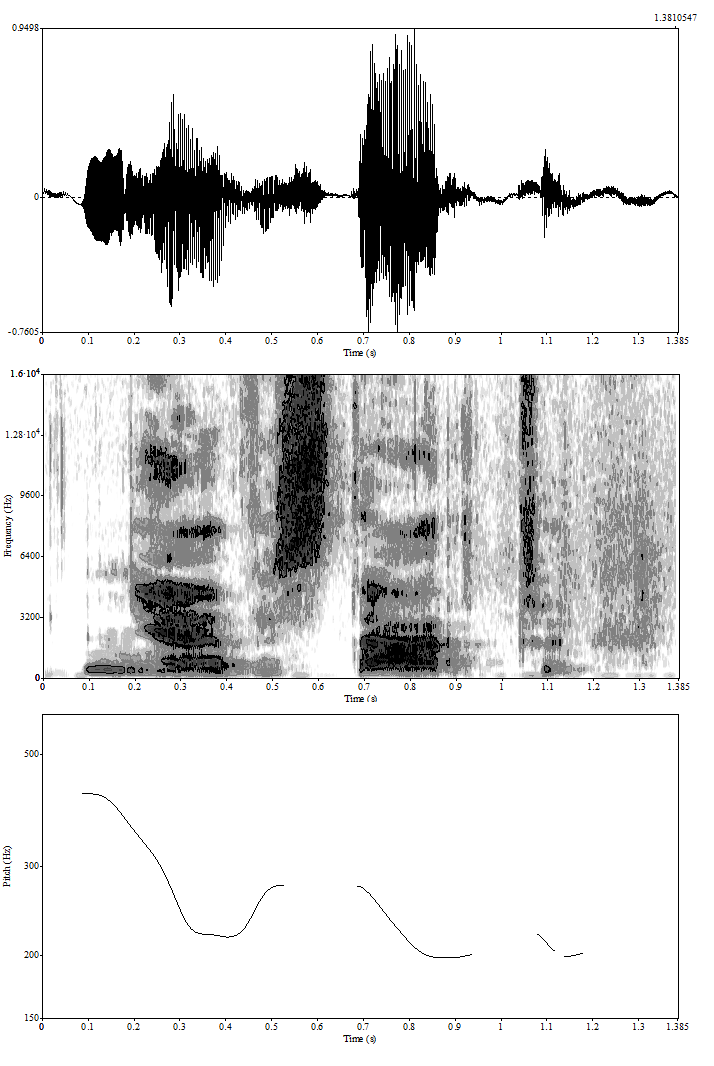

Visible sound

The term may be understood in at least two different ways. Firstly, the simple fact of seeing the speaker’s face greatly enhances the ability to identify and decipher their utterances. This has been proved by, amongst other things, the McGurk effect: seeing the form of the mouth of a speaker influences one’s perception of the sound they produce (try it yourself, for example using this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G-lN8vWm3m0 or this: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jtsfidRq2tw). In a conversation over the phone, even if the sound is of high quality, communicational problems and misunderstandings arise more often than in conversations taking place face-to-face. Visualizations of sound signals, produced by appropriate devices or software, can also be called ‘visible sound’. They are often used in phonetic research. The least technically complicated visualization is an oscillogram. It displays the sound wave propagation in time and changes of the amplitude. It can also be used to approximately identify the sound signal. If the chart resembles a sine wave, it is probably the sound of a flute or a similar simple instrument. In the case of speech, the oscillogram is far more uneven and edgy because of its many overlapping components. The most informative visualization and also, the one used most often by phoneticians, is a spectrogram. Although shown in 2D, it actually represents three dimensional space. It shows how the levels of the respective frequencies vary with time. The vertical axis is the frequency measured in Hz, the horizontal axis represents time. The darker (or in the case of colour spectrograms – usually the redder) the given point on the image, the more energy has been recorded in that particular frequency’s vicinity. Fundamental frequency (f0) is often measured when studying intonation. (f0) is the main factor responsible for the perceived pitch, and by extension, intonation and tonality. The average frequency is between 100 and 150 Hz for men, and between 180 and 230 Hz for women, and even higher for children.

The described methods of visualizations, however, do not highlight what the viewer wants to concentrate on, neither do they omit what she/he cannot perceive anyway. Thus, they do not take the conditions of perception into consideration.

Shown below are examples of an oscillogram, spectrogram and intonogram for the same utterance: ‘nie, wystarczy’ /n’evystart^Sy/ which is Polish for ‘no, enough’ (listen to it: here).

Oscillogram, spectrogram and intonogram for the same utterance: ‘nie, wystarczy’ /n’evystart^Sy/ which is Polish for ‘no, enough’

Less-widely used languages and technology

Language technology is beginning to play an ever increasing role in the documentation of lesser-used languages. Thanks to its developments, one can create systems to synthesise, recognise and interpret speech, expert and dialogue systems as well as software enhancing language learning or computer-assisted translation. For less-widely used languages availability of such programmes is limited since investing into such small, and often economically poor, markets does not bring much profit to large companies. As it seems, however, it is possible to create, for example, speech synthesis systems using the MBROLA on a shoestring budget and without much effort required. They will not rival the latest developments in the area, but they can be fully functional and find many uses. Are you a user of a small, endangered or perhaps simply a less researched language? You can create a speech synthesis system for it on the base of the MBROLA system (homepage: http://tcts.fpms.ac.be/synthesis/). David Gibbon propagated this method in Africa and India. There have been attempts to design such software for languages such as Yoruba [11], Bete [12] (you can listen to a sample here; courtesy of Jolanta Bachan) or Igbo [13]

Notes

[1] Zuni is spoken by about 9,000 people in New Mexico. Find more information here: http://www.amerindianarts.us/articles/zuni_language.shtml

[2] Cheyenne is spoken in Oklahoma and Montana by about 2100 persons. Find more information here: http://www.cheyenneindian.com/cheyenne_language.htm or on endangeredlanguages.com

[3] Indoeuropean, one of the big languages of India.

[4] A language or dialect cluster of the Central Khoisan group of languages, spoken in Namibia. Find more information here: http://www.endangeredlanguages.com/lang/8249 (language name: Khoekhoe), and http://www.ethnologue.com (language name: Nama).

[5] Xhosa is one of the official languages of South Africa. It belongs to the Bantu family and has about 7.8 million speakers.

[6] East Papuan language spoken in Bougainville.

[7] A language spoken in Brazil; Mura family or isolate.

[8] An isolated language spoken in Japan by only a few elderly speakers.

[9] Celtic branch of the Indoeuropean family, official first language of the Republic of Ireland.

[10] Cherokee has about 16000 speakers in Oklahoma and North Carolina. It belongs to the Southern Iroquoian language family.

[11] The Yoruba language belongs to the Niger-Congo language family. It is spoken by around 19 million people in Nigeria and Benin.

[12] An endangered Niger-Congo language spoken in Nigeria.

[13] Another Niger-Congo language of Nigeria, spoken by more than 20 mio people.

References & further reading

- Phonetic/phonological diversification of languages of the world:

- Ladefoged, P., Maddieson, I. 1996. The sounds of the world’s languages. Oxford: Blackwell.

- “Vowels and consonants” – a well-known on-line publication by Peter Ladefoged, introducing the basics of phonetics. It includes samples of sounds from many languages of the world: http://www.phonetics.ucla.edu/vowels/contents.html

- Spoken texts and their IPA-authorised transcription:

- Phonetic transcription and Polish dialects: http://www.gwarypolskie.uw.edu.pl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=72http://web.uvic.ca/ling/resources/ipa/handbook_downloads.htm

- “The North Wind and the Sun” – a story used by phoneticians as a standard text for the purpose of reading: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_North_Wind_and_the_Sun

- If you want to read about intonation of various languages of the world

- Hirst, D., Di Cristo, A. (red.) 1998. Intonation Systems. CUP.

- Speech technology for small languagesSong archives in many languages, recorded on wax cylinders: http://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Ethnographic-wax-cylinders

- Duruibe, U. V. 2010. A Preliminary Igbo text-to-speech application. BA thesis. Ibadan: University of Ibadan.

- Gibbon, D., Pandey, P., Kim Haokip, M. & Bachan, J. 2009. Prosodic issues in synthesising Thadou, a Tibeto-Burman tone language. InterSpeech 2009, Brighton: UK.

- Other used or aforementioned texts:

- Jassem, W. 1973. Podstawy fonetyki akustycznej. Warszawa: PWN.

- Jassem, W. 2003. Illustrations of the IPA: Polish. Journal of the IPA, 33(6)

- Kutsch Lojenga, C. 1994. Ngiti: A Central-Sudanic language of Zaire. Volume 9. Nilo-Saharan. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

- Ostaszewska, D., Tambor, J. 2010. Fonetyka i fonologia współczesnego języka polskiego. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Silverman, D., Lankehship, B., Kirk, P., Ladefoged, P. 1995. Phonetic Structures in Jalapa Mazatec. Anthropological Linguistics, (37), str. 70-88.

Translation from Polish by Arkadiusz Lechocki, translation update: Nicole Nau

back to top